From my recent foray into fermenting drinks with ginger bugs and foraged flowers, I have come to realise a couple of over-generalisations.

Firstly, that the recipes for most of not all fermented drinks take the same shape.

Secondly, that any flavour that works well with sugar can be turned into a fermented drink.

The following is not meant as a treatise about wild fermented drinks, but as a starting point for more experimental thinking on the topic.

The Core Fermented Drink Recipe

- make a must of water, dissolved sugar, and chosen flavours

- Approximately 100g-130g sugar to 1 litre liquid is a good starting point

- simmer for 10-15 minutes, or until satisfied flavours have been extracted

- cool the must and move it to a sizable food-rated plastic or glass container – if a wine, you likely will want a porous cover like a cloth

- add the yeast source, along with an acidic source, like a spoon of vinegar, or half a squeezed lime/lemon

- for a wine, tannins may be desirable – a half cup of long-steeped black tea or raisins or sultanas typically does the trick

- for packet wine or champagne yeast, typically about 1g (like 1/4 teaspoon) per litre of must

- This is the primary ferment started

At this point, two routes, depending on the desired drink. I am typically after a fizz. I am also an impatient sod. It’s enough work to have to repeatedly rack off (pour from one container to another, to leave unwanted bits out), I don’t particularly fancy agonizing over when I will finally be able to drink my creations…

For a fizz:

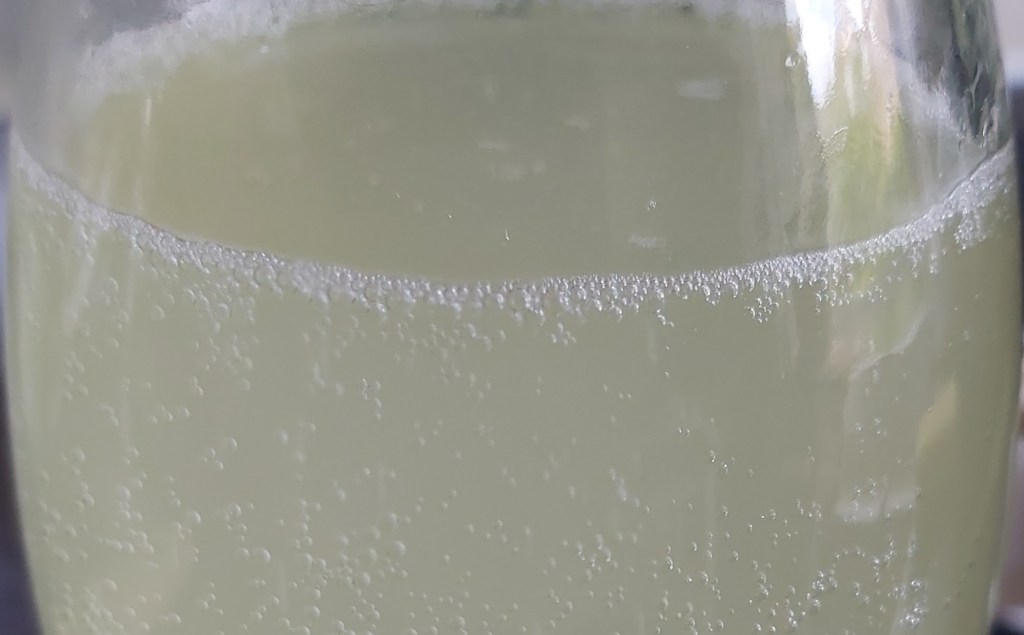

- let it ferment at room temperature for 2-5 days, stirring occasionally, with a sealed top, and burping daily

- rack it off to a big bottle, straining any sediment (“lees”) out

- leave a decent amount of head space for CO2 buildup

- This is now the secondary ferment

- let it ferment at room temperature for 1-3 days, stirring/swirling occasionally. Burp the first few days, and leave it the final day unburped

- for a fizz, rack it off finally to one or several bottles, leaving a bit of headspace for further carbonation safety

- Store on countertop for a day, then move to fridge for 1-7 days

For a wine, I can only really comment on book-knowledge, having yet to complete a full wine.

- Let it ferment at room temperature for 2-5 days, with a cover such that dust, debris and flying insects cannot get in

- rack it off to a big bottle with an air lock, removing any big bits, but retaining some minimal sediment, and let it ferment until the fermentation is complete – anything from 5-10 days or beyond.

- This is now the secondary ferment

- An air-lock is advised usually in this stage, as you can use its bubbling rate as an indicator (try not to have _too_ much air in the top, but some nonetheless). I read consistently that when there’s less than a bubble a minute or two, then most likely the ferment is done

- Now rack it off to individual bottles, seal them, and store them. Wait at least 3 months. If you made only one bottle’s worth, that’s fine too, but you still want to rack off to a new bottle

Pretty much every recipe follows this line. The sugar ratio of course can come down when using particularly sweet fruits. The ratio I averaged out from a handful of recipes for ginger beer and elderflower wine. It’s rounded down around 100g for purpose of mnemonic, but has plenty of wiggle room upwards – the order of magnitude is about right.

If using a flavour source with very dense fibres, some salt (like, a small amount, pinches) may be well-advised. The acid helps fermentation happen, as yeasts favour a slightly more acidic environment. I am told.

A common yeast source is a ginger bug, using its wild yeasts, but elder flowers can be used too – note in this case the typical elderflower wine/fizz recipe does not call for the flowers to be added for the simmer, but after cooling.

Another source again could simply be commercial wine/champagne yeast, awakened first in plain water a few minutes, before being added to the must.

The type of yeast used has various effects, but the ones I find most important at this beginner stage are:

- flavour – bread yeast makes the drink smell like a stale lager after a party. Don’t do it.

- Brewer’s yeast probably would be bready as well, though less so. I have not ued any yet

- Wine yeast is effectual but gentle. The flavour is fairly neatural

- Champagne yeast (as in, from Champagne region) tends to be stronger and drier. It’ll get you a good fizz going fast as I understand it so far

Turn Anything into wine

With knowledge of the core recipe, we can turn to realising that the following all follow that same sequence, with some minor variations on the specifics:

- ginger beer (ginger must + ginger bug or champagne yeast)

- lemonade (sugar and lemon must + ginger bug or champagne yeast)

- elderflower wine (sugar and lemon must + elderflowers as yeast)

- dandelion wine (sugar and dandelion must + ginger bug or wine yeast + tannin source)

- oak leaf wine (oak leaf must + wine yeast + tannin source)

- and various other fruit-based country wines

Anything that can be paired with sweetness can be candidate for wine. The typical head-turner is oak leaf wine which is unusual as a flavour source ; I had a colleague who had an excess of courgettes on the allotment and so resolved to make gallons of courgette wine – I recall him being decently satisfied with the experiment.

The thing is, at the end of the day, the yeasts want sugar. I used a steeping of lady grey once as a must, added the requisite sugar and ginger bug, and let it do its thing. It was a fizzy “iced tea” experience, which I would readily try again.

There is a caveat of making a must form a store-bought fruit juice, as usually these will contain preservatives that would kill any wild yeasts added to it, but some people seem to have still had success.

Another caveat is that this is only safe to apply when dealing with plant materials. Meats, eggs, dairy, and fungi are all out otherwise – they answer to very different processes. The one exception I can think of off the top of my head is honey, which follows the core recipe with sugar being replaced by honey , but needs fermenting for much, much longer by a factor of two or three. I’ve seen it stated that honey is a poor choice for standard fizz ferments, due to the complex natures of the sugars – yeasts take more readily to simpler sugars, apparently. No source, just from memory.

Bug Collection

I’ve seen it asked around before, why is the most popular form of fermentation mother a ginger bug, and not say an “apple bug” or a “raspberry bug”?

It’s on a hunch that I am guessing this:

- ginger, as a root, retains its integrity much better suspended in water – doesn’t disconstruct into the water so easily

- ginger has a zingy flavour which works well for refreshing drinks

- ginger is easy to cultivate in quantity (mostly a historic reason I suppose)

I’ve read of people doing turmeric+ginger bugs with organic turmeric roots. A garlic bug would be wild (but probably on-brand for me…) and since a popular recipe is for garlic preserved in honey, why not give it a try?

One particularly good source of info I’ve found explains the ins and outs of making flower wines in general, and notes the need for extra nutrients for yeast. It may be that some is found on the skin of ginger, but if using just flowers and commercial yeast, raisins seem to be a good choice to add, not only for the tannins, but for the nutrients the yeasts can use to thrive. I wonder if this would be a good thing to standardise into bug making.

Drink the Bug

Recipes are circulating these days about “fruit kvass” which essentially is chopped fruit in water, with sugar, swished and burped daily, until fizzy – sub the fruit for ginger and we simply have a bug! It relies on the wild yeasts of the various fruit skins to activate, and the result is immediately considered a drink – the fruit can even be eaten.

Another drink that is essentially the bug is tepache: instead of ginger, pineapple and spices are used. The solids are eventually strained off, and the liquid is consumed directly. Aside from the pineapple rinds, the rest of the fruit can conceivably stay in the drink to be eaten along the way.

Experiment

All this is getting me revved up for some more experiments. We’re firmly into summer now, and a number of trees are now in bloom. Soon after, autumn will be upon us with berries – even now in the hedgerows, wild raspberries are making an appearance.

Next year I intend to be fully ready for attempting all manner of floral sodas. Sweet bliss.

🍾

Leave a comment